- Home

- Anne Bishop

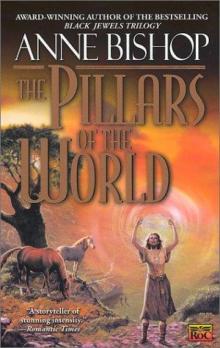

The Pillars of the World ta-1 Page 34

The Pillars of the World ta-1 Read online

Page 34

She put the puppy down and walked over to the sun stallion, patted his neck cautiously. “It’s time to go.”

The stallion pawed the ground.

“Come on, now. Come on. Ahern will look after you.”

The sun stallion shook his head. When Ari walked away and kept going, he and his mares followed. Except the wounded mare. She remained in the meadow, near the spot where the witches of Brightwood had danced year after year.

Ari let her stay. The mare was doing better, and it would be a shame to take her away before the magic in Brightwood had a chance to heal her.

“I’ll let Ahern know she’s here,” Ari told Merle as they crossed the road and headed for Ahern’s farm. “He’ll keep an eye on her.” As she reached the top of the rise, she looked over her shoulder at the horses trailing behind them. “I wonder if a mother duck feels this way when all her ducklings waddle after her.”

The image of a duck being followed by horses who thought they belonged to her made Ari smile. It was best to think of silly things today. It was best not to think at all.

Lucian watched the canopy of leaves over his head play with the sunlight and shadows. This little spot in the garden was always a peaceful place, but today he found no peace there. He kept thinking about the version of “The Lover’s Lament” that Ari had sung on the Solstice.

A song like that was more than folly; it was cruel. Yes, cruel, since it filled a young woman’s head with dreamy-eyed, unreasonable expectations. That wasn’t the way of the world. That wasn’t the way of men.

Is it cruel? something inside him asked. Are those expectations really so unreasonable?

Lucian shifted uneasily.

Kindness? Courtesy? Well, those things weren’t so unreasonable for someone like Ari to want. And he’d already given her those. But respect? She was barely more than a girl. If a man showed her too much deference, she would never have the incentive to improve herself and become more interesting. After all, how much respect could any woman command when the only things she could speak intelligently about were weaving and gardens?

Loyalty? If that was so important to her, he could promise her a kind of loyalty. He could certainly pledge that he would never seek another human female’s company. What he did when he visited other Clans—and he would since he was the Lightbringer— was none of the girl’s business. And since she wouldn’t know what took place in Tir Alainn, it would never trouble her.

Love? A bard’s word to pretty up the truth between men and women. Passion burned bright and hot, but it never burned long. Affection truly was a kinder emotion than this . . . love.

Ari might grieve for a little while once she realized she had to give up her girlhood notion about love, but once she was over it, she would come to appreciate the companionship—and pleasure—he offered.

Lucian headed for the entrance to that little garden.

Soon it would be settled. Ari would stay at Brightwood—and stay with him. And Neall . . . Lucian thought about the Gatherer and smiled. And Neall would be gone.

As soon as Neall spotted the sun stallion, he ran to meet Ari.

“Are you all right?” he asked anxiously, pulling her into his arms and holding on tight.

“I’m fine, Neall,” Ari said, rubbing his back to comfort him. “Truly.”

“When it took you so long to get here, we thought—” He couldn’t say it. He couldn’t put into words what he’d feared because, somehow, that might make it come true.

“It wasn’t long. I had to wait for the biscuits.”

Neall stiffened. He leaned back and stared at her in disbelief. “Biscuits?”

“I thought they would be more practical than bread and stay fresher so that we could—”

“You baked biscuits?”

Ari’s mouth began to set in that stubborn line he knew well. Ignoring it, he grabbed her hand and pulled her toward Ahern’s house. “Let’s just see what Ahern has to say about this.”

“Neall!”

The sun stallion snorted, stamped one foot in warning.

“Back off,” Neall snapped. “If she was one of your mares, you’d nip her for this.”

Ahern was pacing the yard, looking grim enough to subdue even the stubbornest witch.

“She was baking biscuits,” Neall said as soon as he was close enough he didn’t have to shout. Although he was shouting loud enough to have several of the men peer around the buildings to see what was going on.

“Neall!” Ari pulled back, digging in her heels.

As Neall turned, the sun stallion butted him hard enough to break his hold on Ari’s wrist. He and Ari ended up sitting in the dirt, staring at each other between the legs of an angry horse.

Another horse snorted. The sun stallion bolted a short distance, then reared.

Neall looked over his shoulder. Not another horse, but someone no horse would disobey.

“That one must have a bit of the dark horse bloodline in him,” Ahern said. “They aren’t cowed by anything.” He walked over to Ari and held out a hand to help her up. “Biscuits are a fine idea. With some cheese and some of that jam you make, it’ll do for a midday meal tomorrow.”

“That’s exactly what I thought,” Ari grumbled, brushing herself off.

“But the boy’s been worried about you—and he has reason. The Black Coats have arrived in Ridgeley.”

Ari paled.

Neall scrambled to his feet. It hurt to see her eyes so full of fear, but he couldn’t afford to make it sound like something they could dismiss.

“Now,” Ahern said, sounding calm but implacable. “You’re going to stay here. Neall will go to Brightwood for your things. When he returns, the two of you are leaving. The horses are fresh, and that will give you hours of daylight to put some distance between you and the Black Coats.”

“I can’t leave yet,” Ari protested. Her eyes filled with tears. “I can’t. I’m not ready. I haven’t said goodbye.”

“Ari, there’s no time,” Neall snapped.

She looked at both of them, her hands spread in appeal. “I’ll run back. It won’t take long. But I need to do this.”

Neall wanted to scream. She hadn’t seen those men. She hadn’t felt those men. How could he make her understand? “By the Mother’s tits, Ari—”

“Don’t you speak of the Mother that way!”

“—who is there to say goodbye to?” Neall demanded. “Morag? If she’s there when I get there, I’ll tell her. If not, when you don’t return, like as not she’ll come here and Ahern can tell her.”

Ari looked at him with eyes that were suddenly far too old. “I would like to say goodbye to Morag,” she said quietly, “but that’s not the reason I have to go back.” Ari reached for his hand. Her fingers curled around his and held on. “I have to say goodbye to Brightwood, Neall. I have to let go of the land. If I don’t, it will always feel unfinished.”

Neall sagged, defeated. If Ari always looked back on this day with regret, what kind of future would they have? Brightwood would always stand between them. He looked at Ahern, hoping the older man would have some argument against this, but Ahern just stared at the distant hills.

“All right,” Ahern said reluctantly. “You go back. You say your goodbyes. But you do it quick—and then you get in the cottage and stay inside until Neall comes for you. The warding spells around the cottage will protect you, but they won’t help if you go beyond the cottage walls.”

Ari seemed about to protest, but she caught herself and simply nodded. She picked up Merle, handed him to Neall, and said, “You’d better shut him up somewhere so he doesn’t follow me ho—” She pressed her lips together for a moment. “Back to Brightwood.” She gave the puppy one last caress, then turned and ran.

“Come on,” Ahern said. “We’ll shut him up in the gelding’s stall. He’ll be fine there for now.”

Neall hugged the squirming puppy, but it was the man he looked at. “I’ll miss you.”

Ahern shook his head. “Don

’t look back, young Neall. You go and don’t look back.”

“That philosophy the Fae live by makes it very easy not to take responsibility for anything.”

Ahern didn’t speak for a long time. Then, “There are times when it’s an arrogant fool’s excuse. But there are other times when it’s simply the wise thing to do.”

Chapter Thirty-one

Adolfo drained his wineglass. The tavern didn’t offer the same quality of wine as Felston’s wine cellar, but it was sufficient. “We have fortified ourselves for the difficult tasks to come.” And at the baron’s expense. “Let us go to Brightwood and capture the foul creature who lives there so that we can bring her back to the baron’s estate for questioning.”

“Questioning?” Felston glanced around the inn and lowered his voice. “There’s no need for questioning. You have my daughter’s statement and the confession you got from the Gwynn woman yesterday.”

“I have those confessions,” Adolfo agreed, watching the baron pale at the significance of those words. Yes, the baron was going to be most generous when it came to settling his account. “But the witch must confess to her crimes. She must admit her guilt. She must have time to regret the harm she has done. Therefore, she will be taken to the room at your estate my Inquisitors prepared for such questioning, and she will confess.” And then she will die.

Morag paused at the edge of the meadow, watching the wounded mare graze. Ari must have taken the other horses to Ahern’s. She looked to the west, wondering if she should go to that hill where the wind always blew and tell Astra that Ari was leaving.

Astra.

Something had been nagging at her, trying to catch her attention. But meeting Morphia and then trying to persuade the dark horse to gather his courage and go down the shining road again had pushed it aside. Now . . .

Astra. What was it about Astra?

The Fae are the Mother’s Children. But we are the Daughters. We are the Pillars of the World.

Aiden had mentioned something about the Pillars of the World.

The answers are in plain sight, if you choose to look for them.

I want to ask him if he would bring the journals over to his house. I don’t want them left here. . . . My family’s history. Brightwood’s history, really.

“Hurry,” Morag said, pressing her legs against the dark horse’s sides. He galloped across the meadow, right to the kitchen door.

Sliding off his back, Morag threw the kitchen door open. “Ari?” When she got no answer, she closed the door and hurried to the dressing room adjoining Ari’s bedroom. She’d seen the glass-doored bookcase the other day when the sun stallion and the dark horse had played “tease the puppy,” but she hadn’t thought of it since.

She opened the glass doors and pulled out the last journal on the right.

I am Astra, now the Crone of the family. It is with sorrow that I have read the journals of the ones who came before me. We shouldered the burden and then were dismissed from thought—or were treated as paupers who should beg for scraps of affection. We have stayed because we loved the land, and we have stayed out of duty. But duty is a cold bedfellow, and it should no longer be enough to hold us to the land.

Morag read a little further, but there was nothing Astra hadn’t already said to her. She replaced that journal, skipped over several, then pulled out another.

We are the Pillars of the World. The Fae no longer remember what that means. Or else they no longer care and just expect us to continue as we have done for generations. I know why they forgot us. I am old now, but I remember my Fae lover well, the father of my daughter. I remember his charm—and I remember his arrogance. The Fae, he had said, have no equal. And that may be true. It also explains why they don’t want to remember the ones who had been more powerful— and still are, in our own way, more powerful. They do not want to remember that it was the Daughters who had the magic needed to create Tir Alainn, to shape the Otherland out of dreams and the branches of the Mother—and will. As we will it, so mote it be. And so it was. The Fair Land.

They can’t abide that, can’t admit that. If they do, they will have to give up their arrogance, their supreme belief that there is nothing to compare with them. And they do not want to see that they are fading, that they are so much less than they once had been.

Shaken, Morag replaced the journal, selected another. The witches had created Tir Alainn? If that was true, that certainly explained why their disappearance from the Old Places was causing pieces of Tir Alainn to disappear as well.

We are the wiccanfae, the wise Fae. We are the Mother’s Daughters, the living vessels of Her power. We are the wellsprings. All the magic in this world flows through us, from us. Without us, it will die.

Morag leafed through a few more pages, then closed the journal in frustration. Ari would be back soon, and she didn’t think the girl would appreciate someone reading her family’s history without permission. But the answers were here, if only there was time enough to find the right one.

“Why are you the wellsprings? Why are you the Daughters? Why? Why?”

She pulled out another journal, close to the beginning. The book was so old the binding cracked when she opened it. Trying to peer at the pages without opening the book too far, she swore in frustration. The writing was spindly, and the ink had faded so much it was barely legible.

She walked over to the window, where she would have the most light, and carefully opened the journal to the first page. She stared at the words.

I am Jillian, of the House of Gaian.

She closed her eyes, counted to ten, opened her eyes.

The words didn’t change.

I am Jillian, of the House of Gaian.

The House of Gaian. The Clan that had disappeared so long ago. The ones who had been Fae— and more than Fae. Not the Mother’s Children. The Mother’s Daughters. Her branches. The living vessels of Her strength.

“Mother’s mercy,” Morag whispered. Tears filled her eyes. She closed the journal before any could fall and ruin the ink.

The House of Gaian hadn’t been lost. They’d been forgotten because they were the Pillars of the World, and the rest of the Fae hadn’t wanted to remember that they had not created Tir Alainn.

Rubbing her face against her sleeve, Morag gently replaced the journal, then ran out of the cottage. She swung up on the dark horse’s back.

“We have to go back to Tir Alainn. We have to—” Her voice broke. “We have to tell the Lightbringer and the Huntress about the Daughters.”

The dark horse planted his feet, refusing to move.

“We have to go back one more time—for Ari’s sake.”

He hesitated, then leaped forward. She let him have his head, let him race through meadow and woods, let him charge up the shining road to Tir Alainn. She had to get there before Dianna and Lucian did something foolish. She had to make them understand.

Or stop them if there was no other choice.

“Lucian!” Dianna hurried to meet Lucian as he walked out of that private place in the gardens.

Lucian raised his head, reminding her of her shadow hounds when they scent prey. “Have you heard from Morag?”

“Yes, I heard from her.” It was easier now to feel angry when she wasn’t close enough to the Gatherer to feel afraid. “She refuses to help us!”

Lucian stared at her. “She can’t refuse. She’s Fae. And even the Gatherer yields to the Huntress and the Lightbringer.”

“Not according to the Gatherer,” Dianna said bitterly. “Not only did she refuse to help, she threatened me. Me.”

“She’ll regret that,” he said softly.

“Yes, she will.” Dianna felt something inside her slowly untwist. Not even the Gatherer would stand against both leaders of the Fae. Not even the Gatherer would dare. “What do we do about that . . . that Neall?”

“What we should have done in the first place. Take care of the problem ourselves.” He strode toward the stables. “You get your shadow hounds. I�

��ll get your horse. Meet me at the stables and—” He abruptly stopped speaking and pulled Dianna behind a hedge.

“What?” Dianna said impatiently.

“Morag. Riding toward the Clan house.”

“She’s the last person we want to meet right now.”

“Agreed.” Lucian looked at her, a strange excitement shining in his eyes. “So we’ll avoid her.”

They parted, Lucian slipping through the gardens to go the long way around to the stables, and she running to the kennels where her shadow hounds were kept.

Yes, Dianna thought. They would take care of that Neall, and then Ari would have no excuse to leave Brightwood.

Ari stood in the spot where the spiral dance ended— and, in ending, began another kind of dance.

She raised her arms, breathed deep as she began to draw the strength of Brightwood into herself.

The land beneath her feet rolled, spun, swirled, pushed at her as if it were trying to hold in something terrible that was fighting to burst free.

Ari staggered, her arms dropping to help her keep her balance. Stunned, she just stared at the ground that looked no different but felt so strange.

The land doesn’t want me, no longer wants to know me. Can the magic that breathes through Brightwood somehow sense that I’m going away? Is that why I can’t focus it, can’t keep it from shifting and scattering? It tingles beneath my feet the way it does when a bad storm is coming. But the sky is clear.

Shivering despite the warm day, and suddenly uneasy about standing in the meadow, Ari ran to the cottage. As soon as she stepped into the kitchen and closed the door, the fear that made her run like a deer before the hounds disappeared.

She studied the meadow. It looked no different, but something had happened there. The wounded mare had felt it, too, and she was still standing there, watchful.

Maybe the land hadn’t rejected her. Maybe, like Neall and Ahern, it had pushed her toward the place where she was the most protected.

Ari smiled.

Great Mother, I leave this place to those who will come after me. May the land I go to be as generous in its bounty to those who care for it—and are in its care.

The House of Gaian

The House of Gaian Heir to the Shadows

Heir to the Shadows Queen of the Darkness

Queen of the Darkness Shaladors Lady

Shaladors Lady Written in Red

Written in Red Lake Silence

Lake Silence The Voice

The Voice Twilights Dawn

Twilights Dawn Daughter of the Blood

Daughter of the Blood Dreams Made Flesh

Dreams Made Flesh The Shadow Queen

The Shadow Queen Etched in Bone

Etched in Bone Wild Country

Wild Country Vision in Silver

Vision in Silver Sebastian

Sebastian Shadows and Light

Shadows and Light The Queen's Bargain

The Queen's Bargain Bridge of Dreams

Bridge of Dreams The Queen's Weapons

The Queen's Weapons Pillars of the World

Pillars of the World Marked in Flesh

Marked in Flesh Heir to the Shadows dj-2

Heir to the Shadows dj-2 The House of Gaian ta-3

The House of Gaian ta-3 Marked In Flesh (The Others #4)

Marked In Flesh (The Others #4) Dreams Made Flesh bj-5

Dreams Made Flesh bj-5 Written In Red: A Novel of the Others

Written In Red: A Novel of the Others Twilight's Dawn dj-9

Twilight's Dawn dj-9 Shalador's Lady bj-8

Shalador's Lady bj-8 The Pillars of the World

The Pillars of the World Bridge of Dreams e-3

Bridge of Dreams e-3 Tangled Webs bj-6

Tangled Webs bj-6 Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others

Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others Sebastian e-1

Sebastian e-1 Queen of the Darkness bj-3

Queen of the Darkness bj-3 Belladonna e-2

Belladonna e-2 The Invisible Ring bj-4

The Invisible Ring bj-4 The Shadow Queen bj-7

The Shadow Queen bj-7 Shadows and Light ta-2

Shadows and Light ta-2 Daughter of the Blood bj-1

Daughter of the Blood bj-1 The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc)

The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc) The Pillars of the World ta-1

The Pillars of the World ta-1