- Home

Page 2

Page 2

The House of Gaian

The House of Gaian Heir to the Shadows

Heir to the Shadows Queen of the Darkness

Queen of the Darkness Shaladors Lady

Shaladors Lady Written in Red

Written in Red Lake Silence

Lake Silence The Voice

The Voice Twilights Dawn

Twilights Dawn Daughter of the Blood

Daughter of the Blood Dreams Made Flesh

Dreams Made Flesh The Shadow Queen

The Shadow Queen Etched in Bone

Etched in Bone Wild Country

Wild Country Vision in Silver

Vision in Silver Sebastian

Sebastian Shadows and Light

Shadows and Light The Queen's Bargain

The Queen's Bargain Bridge of Dreams

Bridge of Dreams The Queen's Weapons

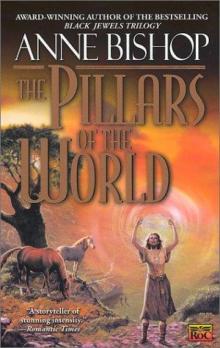

The Queen's Weapons Pillars of the World

Pillars of the World Marked in Flesh

Marked in Flesh Heir to the Shadows dj-2

Heir to the Shadows dj-2 The House of Gaian ta-3

The House of Gaian ta-3 Marked In Flesh (The Others #4)

Marked In Flesh (The Others #4) Dreams Made Flesh bj-5

Dreams Made Flesh bj-5 Written In Red: A Novel of the Others

Written In Red: A Novel of the Others Twilight's Dawn dj-9

Twilight's Dawn dj-9 Shalador's Lady bj-8

Shalador's Lady bj-8 The Pillars of the World

The Pillars of the World Bridge of Dreams e-3

Bridge of Dreams e-3 Tangled Webs bj-6

Tangled Webs bj-6 Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others

Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others Sebastian e-1

Sebastian e-1 Queen of the Darkness bj-3

Queen of the Darkness bj-3 Belladonna e-2

Belladonna e-2 The Invisible Ring bj-4

The Invisible Ring bj-4 The Shadow Queen bj-7

The Shadow Queen bj-7 Shadows and Light ta-2

Shadows and Light ta-2 Daughter of the Blood bj-1

Daughter of the Blood bj-1 The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc)

The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc) The Pillars of the World ta-1

The Pillars of the World ta-1