- Home

- Anne Bishop

The Pillars of the World Page 2

The Pillars of the World Read online

Page 2

“Take care,” he said in that quietly stern voice that the countries of Arktos and Wolfram had already learned to fear. “Do let her wickedness incite you to less than honorable behavior. Her remaining time should be spent in reflection and repentance on the harm she has done the good people of Kylwode and not on any harsh treatment that may come from your hands.”

The men holding the woman hesitated, then nodded.

She fought against their hands, making it impossible to lead her forward without dragging her.

Adolfo fixed his brown eyes on her. “Do not make this more difficult. Accept the fate your own actions have brought you to.” He paused, then added very gently, “Unless you have other things to confess?”

The woman stiffened, her eyes wide and fearful. A moment later, she sagged in her captors’ hands.

They led her to the open grave, keeping their steps small as she shuffled between them as well as the hobbles permitted. When they turned her to face Baron Hirstun and Adolfo, her eyes were filled with loathing for the men who had condemned her. She straightened, a last gesture of defiance that made her look like one of the gentry instead of a frightened, bedraggled woman who was about to die.

Adolfo felt fear creep down his spine, felt it collide with the hatred that had shaped his life until it settled into a dull ache in his lower back. That war within himself didn’t show on his face or in the eyes that always remained as soft and gentle-looking as a doe’s.

But the other men shifted uneasily as they felt the power rising in her.

It’s the last time it will rise, Adolfo reassured himself. And it can’t help her now. I’ve made sure of that. “Do you have any last words?” he asked her.

She said nothing.

One of the men holding her glanced at the metal device around her head. “Begging your pardon, Master Adolfo, but I don’t think she can be saying much with that thing around her head.”

“Get on with it,” Hirstun growled.

Adolfo ignored the baron and addressed the man. “I would know her words no matter how garbled. But the metal tongue on the scold’s bridle prevents her from clear speech, and, therefore, prevents her from casting a last spell to harm those who bring her to justice.”

The other man grinned at the first. “You should get one of those for your Jenny, Sax. Give you a bit of peace.”

Sax ducked his head. “Her tongue’s got a sharp side to it, and that’s the truth, but I couldn’t see putting one of those things on my Jenny.”

“The scold’s bridle is a good man’s tool,” Adolfo said. “A caring husband and father does not allow his females to stray into unseemly behavior, nor does he allow his females to create discord at home. And it is well known that a woman’s sharp words can blight a man’s rod and weaken his seed until all he can fill her with are girl babes instead of strong sons.”

Sax’s face turned bright red. He stared at the ground. “Still, it looks like a harsh thing to do to a woman.”

Adolfo smiled indulgently. “Metal is used for witches. For other women, the scold’s bridle is made of leather, and a man tends it with the same care he gives the bridle of his favorite mare. It does her no harm. The shame of wearing it is sufficient to teach her modesty and pleasing behavior. Even my own cherished wife must, from time to time, wear the bridle. At first she resented and resisted being disciplined. Now she is grateful for that sign of my deep affection and concern for her well-being.” He waited a moment, then added, “But perhaps you do not care quite as much for your Jenny.”

After a long pause, Sax mumbled, “Where could I find one of these bridles?”

“I have copies of the pattern,” Adolfo said. “I’ll see that you get one—when our task is complete.”

He kept his eyes on Sax, but he had been watching the witch, had seen the moment when she could no longer maintain her defiant stance and had slumped once more into the resignation of a dumb animal caught in a trap.

“Bind her legs. Be sure to leave enough leather for the spikes.”

Sax pulled the length of leather from his belt and hunched down. When he reached under her dress, Adolfo snapped, “Bind it over her dress. We do not want any good man standing witness here to be provoked into lust if she should begin thrashing and expose her limbs. Women are weak vessels, easily corrupted by the Evil One. But even a strong man can be snared through the lascivious actions of a woman who is the Evil One’s servant.”

Sax quickly finished tying her and stepped back, rubbing his hands against the rough fabric of his trousers, as if even so little exposure to her might put him in danger.

Adolfo made a slight gesture at the grave. “Put her down. One of you other men get the box from the cart.”

When Sax and his friend lowered her into the grave, she began struggling again. Reluctantly, they slid into the hole to force her onto her back.

“Drive the spikes into the ground and tie the leather to them to keep her legs still,” Adolfo instructed. He gestured to the man who had retrieved the box that had been built to Adolfo’s specifications. “Place the box over her head and shoulders. Fix the other spikes through the straps.”

As soon as Sax and his friend were done, the other men helped them out of the grave.

“Fill it in,” Adolfo said. “Begin at the feet and work toward the head.”

He and the baron watched in silence as the men shoveled dirt into the grave. When the first shovelful of dirt finally hit the wooden box, they heard her scream.

“I wouldn’t have thought the Master Inquisitor was a compassionate man,” Hirstun said quietly. “What difference does it make if the bitch gets dirt in her eyes?”

“I am a compassionate man,” Adolfo said just as quietly. “If I were not, I wouldn’t have taken up the task of freeing good people from these wicked creatures. The box will hold a little air after the grave is filled in. That will give her time to repent.”

Hirstun eyed him warily. “And how will anyone know if she does repent?”

Adolfo smiled sadly. “True repentance comes at the moment before death. If she was spared at that moment, she would swear that she had repented, but it would be a lie. Death is the only freedom these creatures know, Baron, and even that isn’t freedom since their actions in this world have condemned them to the Fiery Pit that awaits the Evil One’s servants.”

They said nothing more until the last shovelful of dirt filled the hole.

“Well, it’s done,” Hirstun said, watching his servant pass out copper coins to the men who had assisted. “You’ll come back to the manor to . . . settle things?”

“I’ll be along shortly. I want to maintain watch for another minute.”

“You are most diligent in your task.” Hirstun walked away, his servant and the common men trailing behind him.

“Yes, I am,” Adolfo said softly once there was no one close enough to hear. “I will not suffer a witch to live.”

She lay in the dark, feeling the weight of the earth pressing down on her. Not much air left, not much time.

She’d tried to summon the power, had tried to move the earth so that she might somehow escape. But it was water, not earth, that was the branch of the Mother from which she drew her strength, and her efforts had gained her nothing.

Why had things changed? Why? For generations, the women in her family and the rest of the people in Kylwode had lived and worked peacefully in each other’s company. How many of the common villagers and tenants on the baron’s land had been helped by her grandmother’s simples when they didn’t have the coin to pay the physician, who was really only interested in tending to the gentry and the merchant families in the area? How many had she helped by showing them where to dig their wells? And this was how they showed their gratitude for all the help that had been given?

She tried to breathe slowly, tried to make the air last, knowing it was useless to hope, and still unable to keep from hoping that some of those men—any of those men her family had helped over the years—would defy Ba

ron Hirstun and return to free her.

Why had resentment begun to simmer in Kylwode? Was it because people had looked at the sparse crops they were scraping out of their own overused land and then had turned envious eyes on the rich meadows and forests—and the game that lived there—that belonged to the women of her family since the first witch had walked the boundaries and marked the Old Place that was in her keeping?

How many years had they been telling people, over and over again, that the Mother was bountiful, but one must give as well as take? The people in Kylwode simply didn’t want to listen. The Mother gave—and should keep on giving and giving. And lately, the response to any suggestion of giving something back to the land was, “witch words,” followed by uneasy, suspicious looks—and the suggestion that the “giving” was some kind of blood sacrifice. And that the bounty of her own garden was payment from the Evil One for carnal pleasures.

She’d never heard of the Evil One until Master Adolfo came to stay with Baron Hirstun. But she knew with absolute certainty that there was such a creature, that the Evil One did, indeed, walk the earth.

And its name was Master Inquisitor Adolfo, the Witch’s Hammer.

He was the very breath of Evil with his quietly spoken words and the gentle sadness in his eyes. Those things were the mask that hid a rotted spirit.

Oh, yes, treat the witch gently so that she may repent. Don’t look upon her limbs so that you won’t be swayed by lust.

The soul-rotted bastard just didn’t want those men to see the welts, the cuts, the burns he had inflicted on her to “help” her confess. The hobbles provided a clever excuse for why she couldn’t walk well. And he certainly hadn’t hesitated to indulge his lust. His rod was as much a tool as the heated poker and the thumbscrews.

Three times he had led her to the small writing table in the hated room in Baron Hirstun’s cellar that he had changed into his Inquisitor’s torture chamber. Three times he had insisted that she must confess her crimes against the good people of Kylwode.

Twice she had refused to sign the confession he had written out, had even demanded the first time to know who had accused her of doing harm. She had done none of the things listed as her “crimes.” Harming others was against the creed she and her family lived by.

Twice she had refused. But the third time, he had shown her the other bridle, the one she would force him to use if she continued to resist his attempt to lead her to repentance. That bridle had what he called “witch stingers”—spikes that would pierce the cheeks and tongue. He had shown her the other things that would have to be used to persuade her to “freely” confess.

When she finally signed the confession, he told her he was grateful she had relieved him of the burden of continuing such an onerous task. And by signing, it was she, and not he, who had condemned her to this death.

Bastard!

Tears filled her eyes.

So hard to breathe now. So very hard.

She was glad her mother and grandmother had gone to a neighboring village to help with a birth when the baron’s men—and Master Adolfo—had come for her. She hoped one of the Small Folk had warned her family while they were still on the road home so that they could flee.

Not much time now. Her body struggled for air.

Water was her strength and her love. But they had planted her in the middle of a dry field on the other side of the village, too far away from the Old Place that had been her home to give her even that much comfort. If only she could feel water flow over her hand once more, maybe she could accept . . .

She dimly heard her own garbled, anguished cry.

Beyond the field, behind a stand of trees, the brook seemed to hesitate. Its bed shuddered and ripped. Then ripped deeper. The water poured into that rip, forcing its way between the trees’ roots until it found a newly made channel that continued to shiver open before it even as it spread itself beneath the land.

Her hand was wet. Not just damp from the earth, but wet.

The water found the open space of the box—and the brook sang to her as it had done so many times.

She closed her eyes and floated on its song.

The water caressed her. She no longer felt her body, no longer felt any pain. Just the water as it continued to rise to the surface—and took her with it.

“This will be enough?” Hirstun said as he studied the confession.

“It has been more than adequate in Arktos and Wolfram,” Adolfo replied. “Sylvalan has a similar law: any person convicted of a heinous crime against the community forfeits all property, which then goes to the highest-ranking noble in the community to dispense as he sees fit.” It was a law Hirstun knew well; at least three of his tenants had once been freeholders before one of Hirstun’s ancestors had found a “crime” against those families that allowed him to confiscate the land and add it to his own holding.

“There’s only one copy,” Hirstun said.

“I retain the other copy,” Adolfo replied. And that copy confessed to one other thing, which would only be brought to light if Hirstun proved to be a difficult man to deal with.

“I expect you’ll be leaving soon.”

That tone, both dismissal and command, infuriated Adolfo, but his voice remained mild when he said, “Unless there are others in Kylwode who are suspected of practicing witchcraft.” He made the words almost a question.

“Those three were the only witches in Kylwode,” Hirstun said coldly.

Which is not the same thing, Adolfo thought. Not the same thing at all. That was the error the gentry in Arktos and Wolfram had made when they had first started dealing with him. They had treated him like a servant once his duties had given them what they wanted. But they had learned, as the gentry in Sylvalan would learn, just how hard the Witch’s Hammer could strike a village, how far the frenzy of accusations could spread with the right incentive, how even a gentry family was not immune.

Hirstun opened a drawer in his desk, pulled out a hand-sized bag of gold coins, and dropped it on the desk.

“When we first discussed the trouble in Kylwode, you agreed to pay two bags of gold for my services,” Adolfo said quietly.

“You only had to deal with one of them, not all three,” Hirstun said sharply. “And the other two won’t be coming back. Half the fee for one-third of the work seems more than fair.”

So that’s how it would be.

Adolfo sat back in his chair, turning his head just enough to look out the window at the baron’s children, who had gathered on the lawn with some of their friends.

“The Evil One is a pernicious adversary,” Adolfo said. “Sometimes a person becomes ensnared without realizing it until she—or he—is persuaded to open her soul and confess. Sometimes a person becomes Evil’s servant through carnal indiscretion. Pain is the only spiritual purge for someone who has been misled by a witch’s lust.”

Hirstun looked out the window, stared at his eldest son for a long moment, then swung back to face Adolfo. “Are you accusing my son of having carnal acts with a witch?”

“Were we speaking of your son?” Adolfo said mildly.

The way Hirstun paled was confirmation enough about why there was a resemblance between the witch they’d just condemned and Hirstun’s daughter.

A long, strained silence hung between them.

Adolfo waited patiently, as he’d done so many times before. He was a middle-aged, balding man who had the lean face of a scholar and the strong body of a common laborer. His clothes, as dull-colored and simply cut as a common man’s, were made of the finest wools, the best linens. His voice held the inflections of a gentry education as well as the roughness of a man whose education had been acquired in the alleys. People like the baron were never sure if he had been a younger son of a prominent family who had fallen on hard times or some backstreet brat who had spent years learning to mimic his betters until he could pass for one of them. While their lack of deference infuriated him, he understood the value of letting the gentry think they were d

ealing with a cur only to discover a wolf had them by the throat.

Finally, reluctantly, Hirstun pulled out another bag of gold.

“My thanks, Baron Hirstun,” Adolfo said. “I do what I must because it’s the task I have been given, but there are expenses to performing that task.”

“You seem to make a good living being the Witch’s Hammer,” Hirstun said, eyeing the small jewels that completely covered the large medallion Adolfo wore over a brown wool tunic and white linen shirt.

Adolfo brushed a finger over the medallion. “I have spent the last thirty years of my life doing this work. Each of these stones represents a village in my homeland that I cleansed of witches—and all other signs of witchcraft.”

“We understand each other well enough,” Hirstun said harshly. “I trust that understanding will continue.”

“That is my hope as well,” Adolfo said, gathering up the bags of gold. “If you will excuse me, Baron, I must send a message to my assistant Inquisitors.”

“Why?”

Adolfo smiled slightly. “The work we do is filled with dangers. It is our custom to inform each other of where we are as well as our next destination. That way, if something should happen to one of us, the others would know where to begin the hunt for the Evil One’s servant.”

“I see,” Hirstun said tightly.

You begin to see, Adolfo thought as he made his bow and left the room. For now, that is enough.

In the gray, predawn light, Morag let the dark horse pick its way across the sodden field toward the young woman sitting on a small mound of earth.

Seeing the fear and tension in the woman’s face, she reined in a few feet away and let a gentle silence build between them.

“You can see me,” the woman said.

Morag’s lips curved in a hint of a smile. “I am the Gatherer. I see all the ghosts.”

The House of Gaian

The House of Gaian Heir to the Shadows

Heir to the Shadows Queen of the Darkness

Queen of the Darkness Shaladors Lady

Shaladors Lady Written in Red

Written in Red Lake Silence

Lake Silence The Voice

The Voice Twilights Dawn

Twilights Dawn Daughter of the Blood

Daughter of the Blood Dreams Made Flesh

Dreams Made Flesh The Shadow Queen

The Shadow Queen Etched in Bone

Etched in Bone Wild Country

Wild Country Vision in Silver

Vision in Silver Sebastian

Sebastian Shadows and Light

Shadows and Light The Queen's Bargain

The Queen's Bargain Bridge of Dreams

Bridge of Dreams The Queen's Weapons

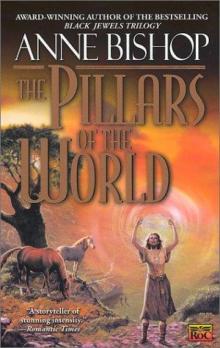

The Queen's Weapons Pillars of the World

Pillars of the World Marked in Flesh

Marked in Flesh Heir to the Shadows dj-2

Heir to the Shadows dj-2 The House of Gaian ta-3

The House of Gaian ta-3 Marked In Flesh (The Others #4)

Marked In Flesh (The Others #4) Dreams Made Flesh bj-5

Dreams Made Flesh bj-5 Written In Red: A Novel of the Others

Written In Red: A Novel of the Others Twilight's Dawn dj-9

Twilight's Dawn dj-9 Shalador's Lady bj-8

Shalador's Lady bj-8 The Pillars of the World

The Pillars of the World Bridge of Dreams e-3

Bridge of Dreams e-3 Tangled Webs bj-6

Tangled Webs bj-6 Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others

Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others Sebastian e-1

Sebastian e-1 Queen of the Darkness bj-3

Queen of the Darkness bj-3 Belladonna e-2

Belladonna e-2 The Invisible Ring bj-4

The Invisible Ring bj-4 The Shadow Queen bj-7

The Shadow Queen bj-7 Shadows and Light ta-2

Shadows and Light ta-2 Daughter of the Blood bj-1

Daughter of the Blood bj-1 The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc)

The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc) The Pillars of the World ta-1

The Pillars of the World ta-1