- Home

- Anne Bishop

Belladonna e-2 Page 2

Belladonna e-2 Read online

Page 2

No. Torry wasn’t like that.

A glass of ale and time with his friends. Are you sure that’s all he wanted at the pub? Maybe he was looking for something more. Or someone like…

Shauna? Everyone knew Shauna was a bit wild, and willing to give the lads more than a few kisses. And she’d had her eye on Torry, even though he’d never noticed.

Oh, he noticed. You’re the one who can’t see.

A dark, bitter feeling rolled through Erinn, followed by a shivery pleasure at the thought of scratching Shauna’s pretty face. No, better than that. She’d scratch the bitch’s eyes out. Then Shauna wouldn’t look so pretty. Then the bitch wouldn’t be casting out lures and spoiling things for decent girls. Then…

Gasping for air, Erinn shook her head. Why was she thinking these things? It was like someone else was inside her head, whispering every uneasy thought that had lodged in her heart since feelings had overruled prudence and she’d let Torry talk her into doing the man-and-woman part of the wedding before making the husband-and-wife vows.

But she loved Torry. And he loved her. And she wasn’t going to listen to these foolish whispers anymore.

Erinn’s hands lifted, closing into fists that gripped the front of her coat as she stared at the dark street. No more streetlamps were lit. There were no lights on in the houses. There was nothing but the dark, which suddenly felt thick, almost smothering—and aware of her.

Nearby, a dog began barking, startling her. Maybe it had caught her scent. The wind was in the right direction.

Or maybe it had caught the scent of something else.

She looked to her right. A service way ran between the buildings. Not wide enough for wagons or carriages, it still provided a cut-through for delivery boys on bicycles and for people who didn’t want to go the long way round in order to reach the main street to do their shopping and such.

Donovan’s Pub wasn’t far from there. She’d go in and ask Torry to walk her home. She didn’t care if he thought she’d come to check up on him. She didn’t care if he thought she was foolish to be afraid of the dark when she’d never been afraid before. Tonight, she was afraid of the dark.

Taking a deep breath that shuddered out of her in something close to a sob, she entered the service way and hurried toward the light at the other end, whispering, “Ladies of the White Isle, hold me in the Light. Ladies of the White Isle, hold me in the Light.”

Halfway through the service way, just beyond the lamplight’s reach, she heard something move. Before she could run, before she could scream, something grabbed her, swung her around, and pinned her against the brick wall of the building. A hand clamped over her mouth.

A fast movement. A ripping sound followed by the feel of chilly air where the coat had suddenly parted. Followed by an odd, shivery feeling as the skin and muscles in her side opened up.

Lady of Light, protect me. Help me.

In the few seconds it took for her body to recognize pain, the knife had moved. Was now resting on her cheekbone, its tip pricking just beneath her left eye.

“Scream,” a smooth voice whispered, “and I’ll take your eye. Tell me what I want to know, and I’ll let you keep your pretty face.”

The hand clamped over her mouth moved. Curled around her throat.

“Please don’t hurt me,” Erinn said, too afraid to do more than whisper.

A man. She could tell that much, but there wasn’t enough light for her to see his face.

“Tell me what you whispered,” he said. “About the White Isle. About the Light.”

“Please let me go. Please don’t—”

“Tell me.”

“T-the White Isle is the Light’s haven. All the Light that keeps Elandar safe from the Dark has its roots there.”

“And where is the White Isle?”

She hesitated a moment—and felt the knife prick the tender skin beneath her eye. “N-north. It’s an island off the eastern coast. Up north.”

The hand around her throat loosened. The knife caressed her cheek but didn’t cut her as he took a step back.

“Who are you?” Foolish question. The less she could tell anyone about him, the safer she would be.

He smiled. She still couldn’t see his face, but she knew he smiled.

“The Eater of the World.”

So he wasn’t going to tell her. That was good. He would go away, and she would be safe. She was hurt bad. She knew that. But it was only one step, maybe two, and she’d be in the light, the glorious light. Her legs felt cold and weak, but she could get to the end of the service way, could get to the main street. Someone would see her and help her. Someone would fetch Torry, and everything would be all right. They would be married at the end of harvest and—

She saw him raise the knife. And she screamed.

Then he rammed the knife into her chest, cutting off the scream. Cutting off hope. Cutting off life.

Voices shouted and boots pounded the cobblestones as men ran toward the service way.

The Eater of the World shifted to Its natural form and flowed beneath the stones, nothing more than a rippling shadow moving toward the main street. One man stumbled as It flowed beneath his feet, and It left a stain on his heart as It passed.

Then It paused as the first man to reach the girl screamed, “Erinn! No!”

Following the channel cut deep into the man’s heart by grief and the shock of seeing his hands covered in the girl’s blood, It stretched out a mental tentacle, slipped into the man’s mind, and whispered, She was here in the service way because of you. This happened because of you.

“No!” But there was something—a tiny seed of doubt, a hint of innocent guilt. Just enough soil for the planting.

Yes, It whispered, putting all of Its dark conviction into the word. This happened because of you.

It retreated, certain Its words would take root and fester, dimming the man’s Light, maybe curdling that Light enough that it would never fully bloom again, scarring the heart enough that the man would never fully love again.

And the Dark currents that flowed in this village would become a little stronger because of that—just as the Dark currents had grown stronger every day since those two boys disappeared. There had been so many hearts eager to hear Its whispers about the boys going into the woods with a man they knew well enough not to fear.

Until the seasons changed, Its death rollers would remain in the sun-warmed river of their own landscape rather than hunt in the cold water of the pond located at the edge of the village’s common pasture. By the time Its creatures came to this landscape, no one would remember the story those boys were telling about a big log that had come alive and pulled a half-grown steer into the water. And by the time the next boy, or man, wandered too close to the pond and died, the fear that lived in these people would be that much riper, that much sweeter. Would resonate with Itself that much better.

It flowed beneath the main street, heading out of the village. People shuddered as It passed unseen, unrecognized for what It was. Its resonance would lodge in their hearts as uneasiness and distrust, making them wonder which of their neighbors had been the person who had held the knife. When they found the body of the lamplighter…

It had been so satisfying to change into a shape with jaws powerful enough to crush bone. So It had crushed the lamplighter, piece by piece. When It tired of playing with Its prey, It had dragged the body into a dark space and fed while the flesh was still succulent…and alive.

Of course, by the time the other humans found the body, the rats would have had their feast as well.

It would return to this place called Dunberry, and when It did, the people would be even more vulnerable to the whispers and seeds It would plant in the dark side of the human heart—the same side that had brought It into being so long ago.

But first, It needed to reach the sea and head north. The hunting in this landscape would be sweeter once It destroyed the Place of Light.

Chapter Three

p

resent

Michael paused outside the door of Shaney’s Tavern and fiercely wished he’d already downed a long glass of whiskey.

The music was out of tune here. Off rhythm. Wrong. Not as bad as Dunberry, but…

Dunberry. What had gone wrong there? All right, so he’d done a little ill-wishing the last time he’d passed through, but the ripe bastard had been cheating at cards and deserved to have some bad luck. It wasn’t as if he’d prospered from it. He just didn’t think it was fair for Torry to lose his stake simply because the boy had had the poor judgment to try to plump up his wedding purse by playing a few hands of cards. And didn’t Torry find a small bag of gold a few days later—gold his grandfather had hidden in the barn and forgotten years ago? That bit of luck-bringing had balanced out the ill-wishing, hadn’t it?

But the girl Torry was going to marry…Stabbed to death, wasn’t she, and so close to help that Torry and his friends had heard her scream.

He’d heard about it fast enough when he came into the village. Just as he heard what wasn’t quite being said. Not about the girl, Erinn, but about two boys who disappeared a few days before she was killed. Someone had seen them going off with a man who wasn’t from Dunberry but was familiar enough to be trusted. What would a man be doing with two young boys that they would need to disappear after he was done with them?

He hadn’t been in Dunberry for weeks, but sooner or later someone would put his face or his clothes on that “familiar enough” man, and it wouldn’t matter that he’d been in another village when those boys had disappeared. Once the villagers decided he was the man, he wouldn’t survive long enough to get a formal hearing.

So he’d snuck away in the wee hours of the morning, putting as much distance between himself and Dunberry as he could before the people began to stir.

He no longer fit the tune of that village. It had turned dark, sharp-edged, sour.

That’s how he heard places and people. They were melodies, harmonies, songs that fit together and gave a village a certain texture and sound. When he fit in with a place, he was another melody, another harmony. And he was the drum that settled the rhythm, fixed the beat.

But not in Dunberry. Not anymore.

The bang of a door or a shutter made him jump, which jangled the pots and pans tied to the outside of his heavy backpack. The sounds scraped nerves that were already raw, and his pounding heart was another thumping rhythm he was sure could be heard by…whatever was out there.

Tucking his walking stick under the arm holding the lantern, he wrapped his fingers around the handle on the tavern’s door. Then he twisted around to look at the thick fog that had turned familiar land into some unnatural place that had no beginning or end.

Didn’t matter if the music was wrong here. He’d beg or barter whatever he had to in order to get out of that fog for a few hours.

Giving the door a tug, he went inside the tavern, pulling off his brown, shapeless hat as he strode to the bar. The pots and pans clattered with each step. Normally he found it a comforting sound, but when he’d been walking toward the village that lay in the center of Foggy Downs, a lantern in one hand and his walking stick in the other, feeling his way like a blind man…The ordinary sound had seemed too loud in that gray world, as if he were calling something toward him that he did not want to see.

“Well, look what stumbled out of the forsaken land,” Shaney said, bracing his hands on the bar.

“Lady of Light,” Michael muttered as he set his hat and lantern on the bar. “I’ve seen fog roll in thick before, but never as bad as this.” Leaning his walking stick against the bar, he shrugged off the straps of the pack, glad to be rid of the weight.

Then he looked around the empty tavern. He could barely make out the tables on the other side of the room since Shaney hadn’t lit any of the lamps except around the bar.

“Is everyone laying low until this blows past?” he asked, rubbing his hand over one bristly cheek. If business was slow and the rooms Shaney rented to travelers were empty, maybe he could barter his way to a bath, or at least enough hot water for a good wash and a shave, as well as a bed for the night.

Shaney put two whiskey glasses on the bar, then reached for a bottle. He poured two shots.

Michael looked at the whiskey, craving the fire that would ease the chill in his bones. But he shook his head. “Since I’m hoping for a meal and a bed tonight, whiskey is a little too rich for my pocket just now.”

“On the house,” Shaney said, sounding as gloomy as the fog. “And you’re welcome to a bed and a share of whatever the Missus is making for the evening meal.”

“That’s generous of you, Shaney,” Michael said, knowing he should be grateful but feeling as if the ground had suddenly turned soft under his feet and a wrong step would sink him.

“Well, maybe you’d be willing to play a bit this evening. I could spread the word that you’re here.”

Picking up a glass of whiskey, Michael took a sip. “I’m flattered you think so highly of my music, but do you really expect people to come out in this for a drink and a few tunes?”

“They’ll come to play a few tunes with you.”

A chill went through him. The music is wrong here, Michael, my lad. Don’t be forgetting that, or what you are, and lower your guard.

He’d been shy of seventeen the first time he’d come to Foggy Downs, and had been on the road and making his own way for almost a year. Over the years since, he’d come to depend on this being a friendly, safe place to stay. If people realized what he was, Foggy Downs would no longer be as safe—or as friendly.

Shaney downed his whiskey, then pulled a rag from under the bar and began polishing the wood. “Do you remember old Bridie?”

Michael rubbed a finger around the rim of his glass. “I remember her. She smoked a pipe, had a laugh that could put sparkle on the sun, and, even at her age, could dance the legs off any man.”

“That pipe,” Shaney murmured, smiling. “She never ran out of leaf for that pipe. She’d be down to her last smoke, and something or someone would always come along to provide her with a new supply of leaf. People would ask her if she had some lucky piece hidden away because, even when bad things happened, some good would come from it. And she always said currents of luck ran through the world, and a light heart and laughter brought her all the good luck she needed.”

A silence fell between them, but it wasn’t the easy breathing space it usually was when neither felt like talking.

Finally, Shaney said, “The first time you came to Foggy Downs, Bridie saw you, heard you play. She took my father aside after you’d gone on down the road, and she told him to look after you whenever you came to our village. Said she had a feeling that we’d be putting her to ground by the spring, and even though she didn’t think you were ready to give up your wandering to put down roots, you were the best chance Foggy Downs had of having a lucky piece once she passed on. So some of us have known what you are—just as we knew what she was.”

Michael downed the rest of the whiskey, wishing it would ease the despair growing inside him. He truly didn’t want to go out in that fog, but he didn’t want to end up being accused of something he didn’t do and die at the hands of a mob either. “I guess I’ll be on my way then.”

Shaney tossed his rag on the bar and gave Michael a look that was equal parts disbelief and annoyance. “Now what part of what I was saying made that pea-sized brain of yours figure we wanted to see the back of you? And what makes you think so little of me that you’d figure I’d ask any man to walk back out in a fog that someone can get lost in when he’s still within reach of his own door?”

Michael said nothing, surprised at how much Shaney’s annoyance gave his heart a scratchy comfort.

“I can’t change what I am,” he said softly.

“No one is asking you to.” Shaney scrubbed his head with his fingers, then smoothed back his hair and sighed. “Something evil passed through Foggy Downs a few days ago. The whole village had a

bad night of it. Children waking up screaming from the nightmares. Babes too young to say what gave them a fright wailing for hours. And the rest of us…It’s a strange feeling to have an old fear come up and grab you by the throat so you come awake with your heart pounding and you don’t quite know where you are. ’Twas a hard night, Michael, and the next morning…” He looked at the fog-shrouded windows.

Michael stared at the windows before turning back to Shaney. “It’s been like that for days?”

“First couple of days, folks went about their business as best they could, taking care of only what was needed, sure the fog would burn off to what we’re used to having here. The Missus and I even had folks gather here that first night. Had us a grand party, with music and dancing, while we all tried to put aside the bad dreams of the night before. But the fog didn’t lift. Hasn’t lifted. And I’m thinking this fog is more than fog, and if evil used some kind of…magic…to create it, then it’s going to take another kind of magic to put things back the way they were.”

The two men studied each other. Then Michael pressed his hands on the bar and closed his eyes.

He had no words for what he sensed, what he could feel. But the sound that filled his mind was a grating, creaking, sloshing, oozing, tearing. The sound of poison. The sound of old hurts, painful memories, deeply buried fears.

Then he imagined his music filling Shaney’s Tavern, the bright notes of the tin whistle shining in the night like sparkles of sunlight. Certainty shivered through him. His music would shift the balance enough so the people here would be able to heal Foggy Downs. He could reestablish the beat. Fix the rhythm. Restore the balance enough to still belong.

He opened his eyes and looked at Shaney. “You put out the word, and I’ll provide the music.”

Shaney put out the word, and the people gathered. No one from the outlying farms, to be sure, but the families who lived close enough to the tavern to brave the fog came with a covered dish to pass around and children in tow. So Michael listened to gossip and passed along news from the other villages he’d visited during this circuit of wandering. He ate a bit of everything so no lady would be offended and pretended not to notice the speculative looks a few of the young women were giving him. He was used to those looks. Since he was a healthy, fit man who rarely stayed more than a few days in a place, certain kinds of women often looked at him like a savory dish that was only available a few times a year, which enhanced the appeal, and there were a few young widows who were willing to offer him more than just lodging when he came to their town.

The House of Gaian

The House of Gaian Heir to the Shadows

Heir to the Shadows Queen of the Darkness

Queen of the Darkness Shaladors Lady

Shaladors Lady Written in Red

Written in Red Lake Silence

Lake Silence The Voice

The Voice Twilights Dawn

Twilights Dawn Daughter of the Blood

Daughter of the Blood Dreams Made Flesh

Dreams Made Flesh The Shadow Queen

The Shadow Queen Etched in Bone

Etched in Bone Wild Country

Wild Country Vision in Silver

Vision in Silver Sebastian

Sebastian Shadows and Light

Shadows and Light The Queen's Bargain

The Queen's Bargain Bridge of Dreams

Bridge of Dreams The Queen's Weapons

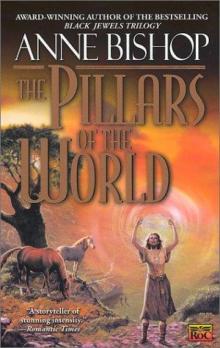

The Queen's Weapons Pillars of the World

Pillars of the World Marked in Flesh

Marked in Flesh Heir to the Shadows dj-2

Heir to the Shadows dj-2 The House of Gaian ta-3

The House of Gaian ta-3 Marked In Flesh (The Others #4)

Marked In Flesh (The Others #4) Dreams Made Flesh bj-5

Dreams Made Flesh bj-5 Written In Red: A Novel of the Others

Written In Red: A Novel of the Others Twilight's Dawn dj-9

Twilight's Dawn dj-9 Shalador's Lady bj-8

Shalador's Lady bj-8 The Pillars of the World

The Pillars of the World Bridge of Dreams e-3

Bridge of Dreams e-3 Tangled Webs bj-6

Tangled Webs bj-6 Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others

Murder of Crows: A Novel of the Others Sebastian e-1

Sebastian e-1 Queen of the Darkness bj-3

Queen of the Darkness bj-3 Belladonna e-2

Belladonna e-2 The Invisible Ring bj-4

The Invisible Ring bj-4 The Shadow Queen bj-7

The Shadow Queen bj-7 Shadows and Light ta-2

Shadows and Light ta-2 Daughter of the Blood bj-1

Daughter of the Blood bj-1 The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc)

The Voice: An Ephemera Novella(An eSpecial from Roc) The Pillars of the World ta-1

The Pillars of the World ta-1